Boston: Who Should Pay For The Big Solutions?

Boston residents are reminded several times a year of their coastline’s vulnerability. King tides flood the city’s Long Wharf and North End areas each year on sunny days and are expected to become even more frequent. An early 2018 storm flooded streets in Boston’s Seaport development hot spot with icy seawater. The city’s planning agency even requires developers to feature local benefits on their construction signage: The developer St. Regis Residences, Boston, includes 100-year flood-proofing as one benefit on theirs.

Boston has a plan to protect $80B of real estate most vulnerable to climate change. But full implementation is decades away, and some argue the most ambitious solutions are being ignored. A lack of leadership on issues around climate change from the federal government is a big reason why long-term measures seem out of reach.

In the meantime, the areas most at risk are also those seeing huge amounts of new development.

The Climate Ready Boston master plan outlines how to protect the city’s biggest development zones, historic building stock and neighborhoods from anticipated flooding, extreme heat and other environmental variables in the future. But it isn’t clear who should be stuck with the bill in implementing change.

According to analysis firm Climate Central, rising sea levels make it roughly 50/50 that Boston will experience a flood of 5 feet above current sea levels by 2030, which would affect property valued at $24B. The chance of that flood happening by 2050: 100%.

A key piece of the city’s climate resilience planning calls for private landowners, especially those with waterfront property, to chip in toward creating a network of parks and sea walls to protect the city from a rising sea level. Private landowners do not typically jump at the prospect of being forced to pay for public infrastructure where the benefits are not immediately accretive to their own specific assets, but Boston leaders are encouraged by the initial response.

The city of Boston is still determining the appropriate metric to price landowners who indirectly benefit from the planned coastal upgrades compared to landowners with property directly on the water.

“The biggest issue is figuring out the equity aspect and how much one should contribute,” City of Boston Chief of Environment, Energy and Open Space Chris Cook said. “What is someone’s fair share?”

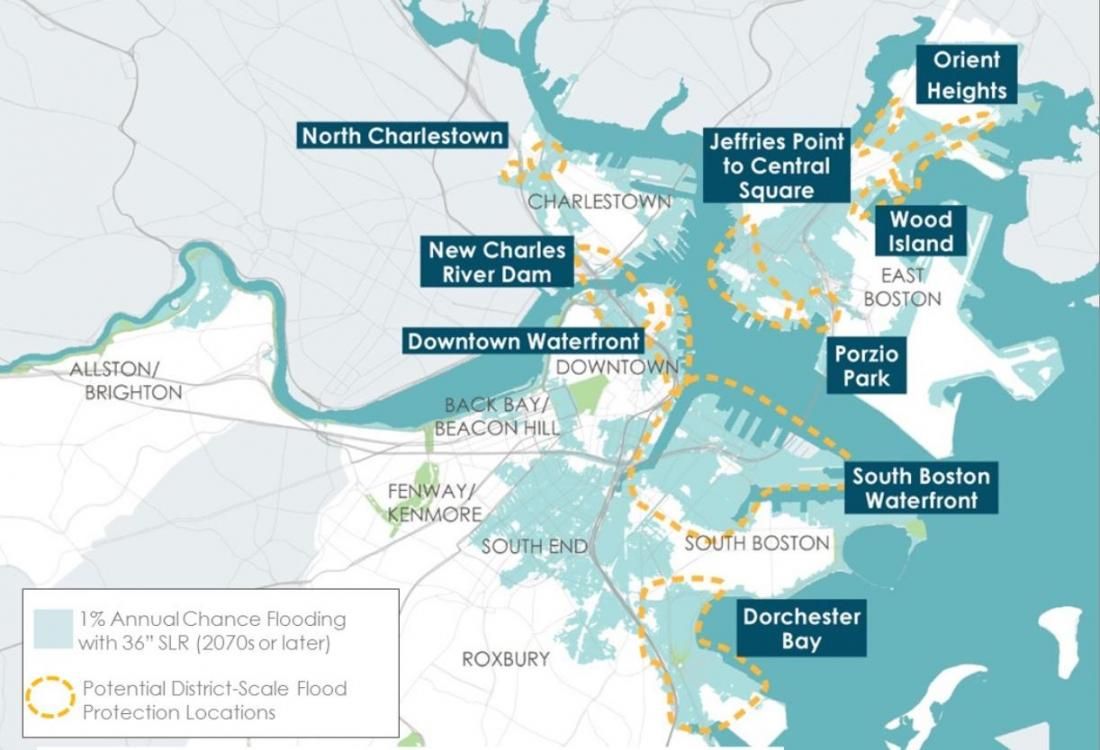

Climate Ready Boston outlines a variety of measures needed to protect 47 miles of Boston coastline as well as inland neighborhoods still vulnerable to future flooding. But when Boston Mayor Martin Walsh announced an extension of the plan called Resilient Boston Harbor, the private sector was asked to pay for a big chunk of the infrastructure being proposed.

That plan calls for civic-led infrastructure upgrades like raising city streets in the Dorchester and South Boston neighborhood. But it also recommends adding 67 acres of green space and seawalls — much of which is on privately owned sections of the city’s Harborwalk waterfront trail. Given the limited number of federal dollars for climate change initiatives, city officials have turned to public-private partnerships to raise funding.

Lendlease built climate-resilient items at its Clippership Wharf waterfront project in East Boston like an elevated portion of the city’s Harborwalk and deployable flood systems that work in an integrated way and benefit multiple neighboring property owners, Cook said.

The planned second phase of General Electric’s Fort Point Channel headquarters, sold to National Development and Alexandria Real Estate Equities following GE’s financial woes, included plans for a living sea wall and green space to absorb flooding from the channel. Those plans remain in National Development and Alexandria’s ongoing proposal for the property.

Blocks away, the Boston Children’s Museum has responded to Walsh’s call for private backing to climate change. The museum’s board launched a climate resilience initiative in 2019 aimed at protecting its stretch of Fort Point Channel waterfront as well as the surrounding blocks of its property.

“They could do the simple thing and protect themselves and their own perimeter,” said Sasaki associate principal and planner Kate Tooke, who is currently working on the plan and also worked on creating the Climate Ready Boston plan. “Instead, they’re saying, ‘We’re part of the solution and [a] contributing member in our neighborhood and value our relationship with that community, so we’re going to implement a solution to protect ourselves and the surrounding community.’”

Before the direct focus on private property and the shore, Boston had previously considered solutions to rising sea levels akin to more climate-conscious countries across the Atlantic.

Superstorm Sandy’s $19B impact on New York City propelled a conversation on what would happen if a similar tropical storm struck Boston and its flood-prone streets. Much of the $80B in Boston real estate that the mayor’s office identified as most vulnerable to rising sea levels is found in the Seaport, the city’s newest development zone, where companies like Amazon, PwC and Vertex Pharmaceuticals all have headquarters or a significant presence.

“The entire world reacts to things when they come to the breaking point and usually not until then. It seems with housing and transportation, we’ve hit that, so we’re focused on that,” CBT principal Kishore Varanasi said. “My hope is we don’t do the same thing with climate because the breaking point could be really bad. You don’t want to wait for that to prepare.”

Climate Ready Boston initially considered a 4-mile protective storm barrier across Boston Harbor from a peninsula north of Boston Logan International Airport to Hull, Massachusetts. Unlike a dam, the barrier, which would be similar to ones in place in Russia and the Netherlands, would have openings for ships to pass through but also gates that could close in the event of a storm like Sandy.

But barriers don’t come cheap. Depending on the configuration, the Boston coastal barrier is estimated to run between $6.5B and $11.8B, according to a 2018 UMass Boston estimate. In Miami, a 267-mile coastal barrier network was projected to cost $3.2B. A sea wall just for the Cape Cod town of Barnstable, Massachusetts, was estimated to cost nearly $890M.

Boston officials like Cook said they would only move ahead on the coastal barrier network if its benefits significantly outweighed its cost. But they also said something like that would take decades of planning, environmental review and approval before getting a green light. A 2018 UMass Boston study found a harbor barrier would be less effective and significantly costlier than a shore-based climate resiliency solution.

Climate experts argue it may be worth it, as more real estate is added to the $80B already identified by the city in its resiliency report.

“We need to keep all ideas on the table. I don’t think we should prematurely write off one thing,” Varanasi said. “We just may have to do it 15, 20 or 30 years from now.”

For now, Boston leaders are focused on the tools they do have readily at their disposal. Ten percent of Boston’s total capital budget has been earmarked for resilience projects since Walsh released the Resilient Boston Harbor plan. Massachusetts’ Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness program also offers grants that go toward planning and implementation of climate change plans.

But federal help is still at the top of the wish list, and it may not come until there is new leadership in Washington.

“Long-term, as you start to look at the GDP of this country, it is still these coastal cities and ports of entry that drive the economy of the United States. We do need federal leadership on these adaptation structures,” Cook said. “It is our hope that, as climate leadership returns to Washington, D.C., there would be some sort of federal funding for these adaptation strategies.”

Property owners in Boston are to some degree willing to pay toward schemes that contribute to a good that extends beyond their own front door, showing a level of big-picture thinking that can often be lacking in the business world, where fiduciary duty toward shareholders is the overriding concern. But even when that is the case, the big, long-term solutions remain elusive, because of failures to think in a structural way.

CORRECTION, FEB. 19, 11:20 A.M. ET: In an earlier version of this story we characterized information from the developer of the St. Regis Residences as marketing. Publicly displayed information about the resiliency of a scheme to climate change is required from the Boston Planning & Development Agency. We have updated the story with this context.

CORRECTION, FEB. 26, 7.35 A.M. ET: In an earlier version of this story we attributed a comment to Sasaki associate principal and planner Joanna Chow. The comment was actually made by Sasaki associate principal and planner Kate Tooke.