Residents Grapple With Change Coming To View Park, LA's 'Black Beverly Hills'

Gilbert Wright remembers playing football on the street with Ike and Tina Turner’s children.

He hung out with the kids of former professional baseball player Curt Flood, who lived up the street.

He knew a member of The Platters or another popular black music group lived down the road. Musician Ray Charles lived nearby on South Ridge Avenue. Dancer Debbie Allen had a home in the neighborhood; so did former Los Angeles Lakers star Michael Cooper.

His other neighbors were mostly African-American professionals — judges, lawyers, doctors, architects, business people and police officers, he said.

Growing up, he said, it was a glorious time to live in View Park. The hilltop community nicknamed the Black Beverly Hills of Los Angeles, along with nearby neighborhoods Ladera Heights, Windsor Hills and Baldwin Hills, made up one of the most affluent predominantly African-American enclaves in the nation.

The Wrights in 1963 were among the first African-Americans to move into the View Park neighborhood, said Wright's 90-year-old mom, Peggy.

“When you’re a kid you don’t realize the environment that you’re living in,” said Gilbert Wright, a 55-year-old attorney in the Los Angeles District Attorney's office, who recently moved back to View Park.

“To me, it just felt like a middle-class existence,” he said. “I had both my mom and dad. The kids in the neighborhood all wanted to go to college. As I got older, that’s when I realized that it wasn’t like that in all of the black communities.”

But times are changing in the neighborhood.

With soaring home prices, the dearth of housing in Los Angeles and huge homes with large lots and the area’s attractive central location, more non-African-Americans are moving in.

Not that it is a bad thing, Wright said.

“It’s a trip,” Gilbert Wright said. “These are the people that moved out when blacks started moving in and now, they are moving back but for a hefty price.”

Peggy Wright said she thinks these are the kids or grandkids of those first white parents who lived in View Park that remember the beauty of this area.

"They want to move back here," she said inside her quaint home on Olympiad Drive.

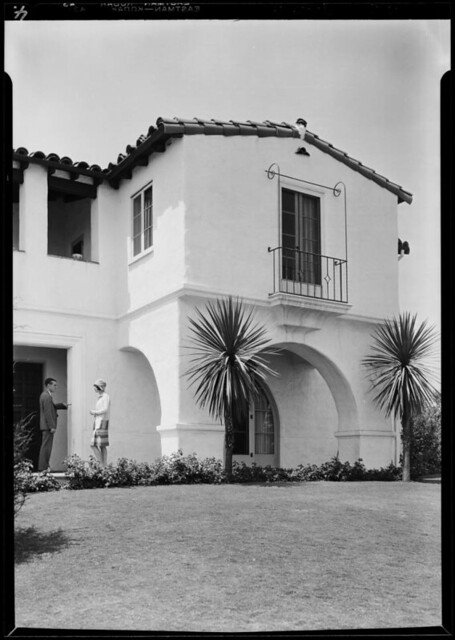

With its tree-lined sidewalks, wide streets, manicured lawns and distinctive architectural homes, View Park is a hillside neighborhood that overlooks parts of Los Angeles.

A breeze comes from the ocean and on a clear day residents say they can see parts of downtown Los Angeles.

The unincorporated area sits in between Crenshaw and Inglewood and within 10 miles east of Silicon Beach (Santa Monica, Venice and Playa Vista) and west of downtown Los Angeles.

"It's a 10- to 15-minute drive from everything — the beach, the airport, downtown LA, wherever you need to go," said Steve Hearn, who has lived on Olympiad Drive since 1983.

The Los Angeles Investment Co., one of the largest home developers in Los Angeles in the early 1900s, began developing the View Park-Windsor Hills area in the mid-1920s and marketed the homes to middle-class and affluent white families looking to live in a suburb-like neighborhood within the hustle and bustle of city life.

According to the Los Angeles Conservancy, a nonprofit whose mission is to preserve architectural and cultural significant areas in Los Angeles, View Park hosted the athletes in the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Back at a time when the Olympic Village was nothing more than just a collection of tents, rows of small bungalows that housed male athletes from around the world lined a street on what is now known as Olympiad Drive.

Shortly after the games, the Los Angeles Investment Co. purchased more land and ramped up construction.

The neighborhood is a collection of about 1,800 mostly single-family Spanish Colonial, Mediterranean and midcentury homes and mansions ranging in lot size from 5K SF to more than 10K SF.

Some of the architecture that dots the neighborhood came from a who’s who of prominent Los Angeles architects such as Postle & Postle, the company that designed the Brooklyn State Bank. Later notable architects were commissioned to design homes, including Paul Williams, Robert Earl and Charles Wong.

At that time, View Park had predominantly Caucasian, white-collar residents. Non-whites who lived in the neighborhood were servants.

View Park like many neighborhoods throughout Los Angeles County at the time had racially restrictive covenants barring non-whites from owning property in the area.

“During that time, there was a lot of discrimination,” Inglewood-based Team Equity L.A. Property & Management President Charles “Butch” Grimes said. “These were legally enforceable title reports. If you read some of the deeds today, they still exist, it’s just not enforceable.”

Grimes, a past president of the California Association of Real Estate Brokers who works with the Los Angeles African-American community, said African-Americans began moving into View Park in the 1950s shortly after the Supreme Court struck down the racial covenants as unconstitutional.

The court ruling in 1948 gave African-Americans and minorities an opportunity to buy homes in View Park and other neighborhoods across Los Angeles, Grimes said.

“You just had to look at the people who lived on the bottom of the hill,” Grimes said. “They worked hard and slowly made their way up the hill.”

Though it was an opportune time for African-Americans and minorities to purchase a home, not all of their neighbors were welcoming.

In 1957, school teachers and African-American twin sisters Evangeline Woods Johnson and Elly Redmond moved into a home on Olympiad Drive in View Park.

The two were met immediately with hostility, with some people marching in front of their home yelling racial slurs. Bricks were thrown at their doors and windows. They received calls and letters of death threats and a week after they moved in, they found a seven-foot burning cross staked on their lawn, according to a June 27, 1957, newspaper account from the California Eagle, an African-American newspaper at the time.

“I want them to know we're not running,” Woods Johnson reportedly said. “This is a thing we're going to have to fight.”

The Eagle said the Los Angeles sheriff’s department downplayed the incident as mere “pranks” by juveniles.

When Peggy Wright moved into the neighborhood in the early 1960s, she recalls getting off the bus and a woman accosting her for stepping on the woman's lawn as she went toward the sidewalk.

"I still remember her looking down at me from the second-floor balcony of her home," said Peggy Wright, who worked as a nurse at a hospital. "It was as if she knew what time I'd get off the bus. After that, my husband would pick me up from the bus stop and drive us to our house."

One night when Peggy Wright was taking out the garbage, she saw her white neighbor and smiled politely. The neighbor gave Peggy Wright an angry scowl and stuck her tongue out.

"Oh. It's going to be like that, OK," recalled Peggy Wright, shaking her head and chuckling at the absurdity of her neighbor's exchange. "From then on, I was going to raise my kids and I wouldn't take that kind of mess."

"It was actually pretty sad," said Peggy's daughter, Claire Traylor, who is now in her late 50s. "I remember we had white neighbors who had kids that were the same age as my younger brother and sister and you could tell their kids wanted to play with them but their parents wouldn't allow it."

By the 1960s and 1970s, white flight began to take place in View Park.

"What my dad told us, it wasn't just one or two white families that would move out, it was like the whole block got up and left," Gilbert Wright said. "There were a few, but not many stayed."

As whites moved out, in the subsequent decades, many African-American professionals and celebrities began moving in and raising their families.

Some of The Mills Brothers had a home in the neighborhood, residents said. Jazz singer Nancy Wilson lived there for a time, too.

Architects, musicians, attorneys, doctors, educators and many more African-American professionals flocked to the area, Grimes said.

“That’s how View Park got its name, 'The Black Beverly Hills,’” Grimes said. “It became a status symbol for the African-American community.”

By 1980, black residents outnumbered white residents 9 to 1, according to the Los Angeles Conservancy. The latest census reported 84% of the 11,000 residents were African-Americans and the population had a median household income of $86K.

Today, View Park is less known for its Black Beverly Hills moniker and more known for its large spacious homes, many with maid quarters and pools.

It is a rarity to find a home in Los Angeles with such a large lot outside of Beverly Hills, Bel-Air and Brentwood for less than $1M, Pacific Union Realtor Amy Andreini said.

“It’s a hidden gem,” said Pacific Union Broker Associate Yolanda Caldwell, who works with Andreini. “You don’t have a lot of traffic. It’s a family-oriented area where neighbors know each other.”

In 2016, the National Park Service, citing View Park's unique history, added it to the National Register of Historic Places. The designation recognizes the neighborhood as a historically black community and allows residents to qualify for tax credits for maintaining their homes.

The designation, along with a surge of commercial real estate developments and a new under-construction Metro line along Crenshaw Boulevard that will pass through areas below View Park such as Baldwin Hills, Leimert Park and other neighborhoods, caused some fears among a small, vocal minority that African-Americans could eventually be priced out of the neighborhood, according to the LA Times.

Since 2011, home prices in View Park have risen by as much as 61%, the Times reported.

"We have so few areas," author and community advocate Earl Ofari Hutchinson, who lives in the neighborhood, said to the LA Times. "So little turf that we can call our own. This is yet another invasion by another group coming in to destroy both the culture, the lifestyle and the economic continuity of our area."

Some call it gentrification, but Andreini, who sold the highest-price home in View Park last year for $1.6M, called it diversification.

"This is not gentrification," Andreini said. "No one is coming in here to improve the area. The neighborhood is beautiful as is. It is diversifying it.

"It's no different than anywhere else in LA," she said. "People are open to it. People don't want to live in their little bubbles anymore. They want to live and learn from the other cultures around them. It adds value to their lives."

With many tech workers being priced out of Silicon Beach, View Park's central location has become a sensible and affordable option, several agents said.

"You look at what happened in Silicon Valley," Grimes said. "Those guys got priced out and where did the tech workers start settling? Oakland, another historical black community. With the rail line on Crenshaw, more people are going to come."

Caldwell and Andreini recently held a one day open house for a home on Olympiad Drive. More than 200 people showed up. They have already received several offers.

Residents say change is inevitable.

Sean Banks, who grew up in nearby Baldwin Hills and now works as an ombudsman for Shell Oil Co. in Houston, purchased a vacation home in View Park in 2012 that he is now selling.

As an African-American, he said he bought the home so his children could be close to their relatives in Los Angeles and spend their summer and winter vacations in a strong and positive African-American community.

"People are friendly. We all know our neighbors on the street," Banks said. "This was not the negative stereotypical black community that you'd see in movies or TV with crime, gang activity or people not contributing to society. It’s not a ghetto.

"The homes are beautiful. People take care of their lawns and landscaping and really created a positive, successful community," he said.

Hearn, a retired diesel mechanic for LA Metro, said growing up in a surrounding neighborhood, View Park provided motivation for him to work harder so he could move his family there.

"To be honest with you, when I was younger, you had to have a reason to be here if you weren’t a resident," Hearn said. "I knew there were celebrities and professionals that lived here. It was a secluded area on the hill. I told myself, one day I'm going to live here. And I'm here."

Residents said they have seen more white and Asian residents moving into the community.

Gilbert Wright, the attorney, said people have every right to live where they want to live and sell to whomever they want to.

However, he laments that many African-Americans do not have the economic means to buy in the area.

"It was a source of pride growing up in a predominantly affluent African-American community," Wright said. "But that is changing and I don’t think there's any way to stop it.”

Banks said selling his home in View Park is bittersweet. He believes bringing more diverse people in the neighborhood will bring the community together.

“I think what you are going to see is that the area is going to look like LA," Banks said. "There is such a strong sense of history for African-Americans. It’s not going to disappear. Gentrification has often caused tension in the community but it will work its way out.

"View Park will look like how LA should look — a diverse and positive community.”

Check out a slideshow of past and present photos of the View Park neighborhood of Los Angeles:

CORRECTION, FEB. 22, 4:45 P.M. PT: A previous version of this story had jazz singer Nancy Wilson's name wrong. The story has been updated.